Bangladesh’s Military Blocks Transparency Push Into Secret Detention Centers

- Hasan Al Manzur

- 06 Feb, 2025

For more than a decade, Bangladesh’s security forces denied the existence of secret detention centers, dismissing reports of enforced disappearances as “political propaganda.” Families of those who vanished were left to wonder if their loved ones were dead or alive, their desperate pleas met with silence or veiled threats.

Now, with the ouster of longtime fascist Sheikh Hasina, the veil is lifting. Survivors of these hidden prisons—facilities where political dissidents, journalists, and activists were held in secret prison for years—are speaking for the first time. Their accounts, stark and horrifying, have revived demands for accountability in a country long accustomed to impunity.

The interim government, led by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, had promised a thorough investigation. A long-anticipated public inspection of these detention sites, including the notorious Aynaghar—or “House of Mirrors”—was set to take place in February, with journalists, human rights groups, and survivors invited to witness firsthand the conditions inside.

But that plan is now in disarray. Four senior officials familiar with the matter say the military, which retains significant power in Bangladesh’s security operations, has objected to allowing journalists and survivors inside the facilities. The move has reinforced concerns that, despite Hasina’s removal from power, the country’s security forces remain beyond civilian oversight, reports Netra News.

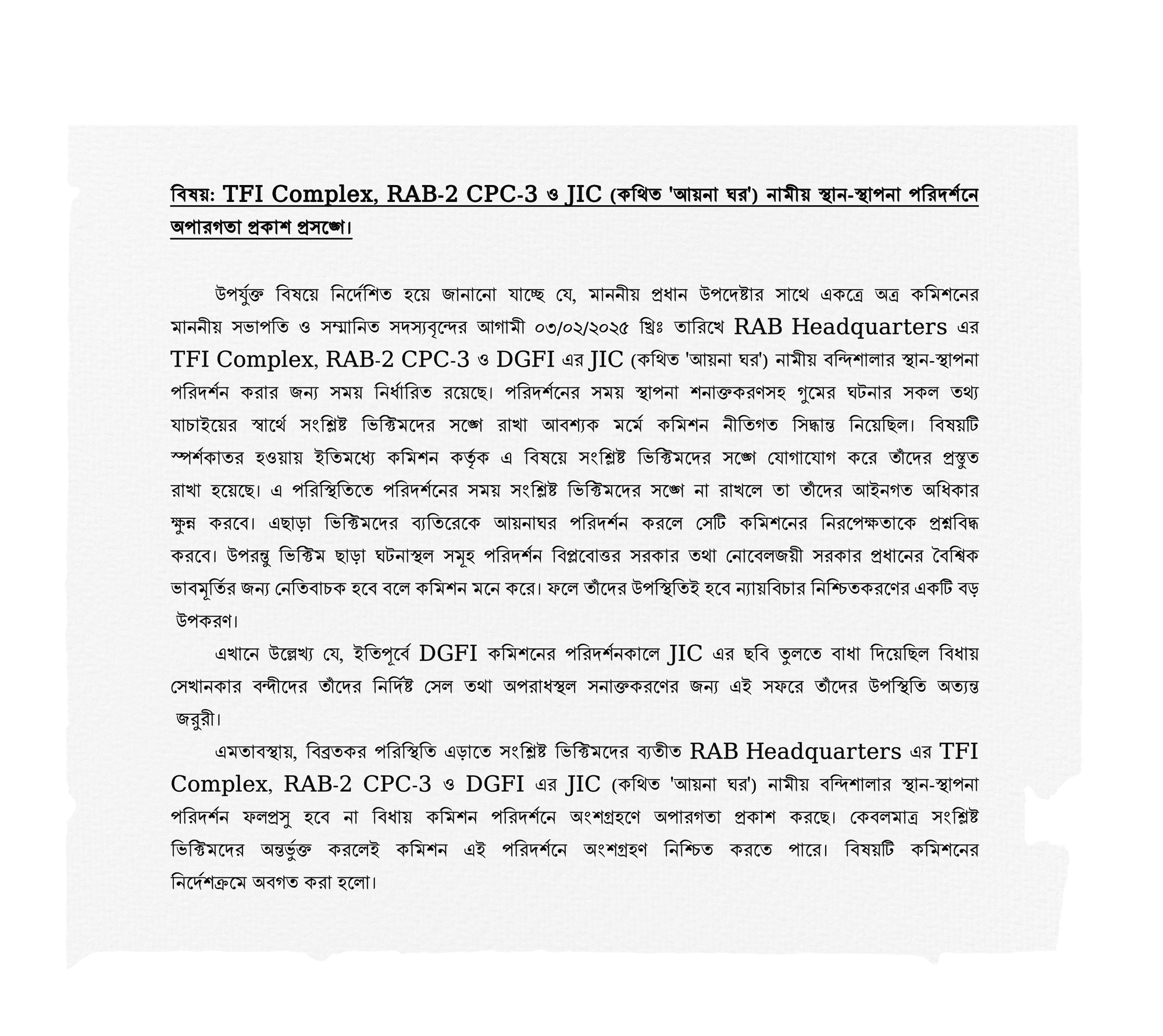

January 29th memo: Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearance refuses to visit secret detention centres without survivors.

The reversal has been met with outrage from human rights organizations and families of the disappeared, who fear the window for accountability is closing fast.

“This was our chance to finally see the truth,” said Afroza Islam Akhi, cofounder of Mayer Daak, an advocacy group for families of the disappeared. “Now we are being told, once again, that the truth must remain hidden.”

A Secret Network of Prisons

The sites in question are not officially recognized. There are no public records of their existence, no legal documents that acknowledge them. But survivors, human rights groups, and journalists have long documented their presence.

Aynaghar, the most infamous of these facilities, was first exposed by the Sweden-based investigative outlet Netra News in 2021. Located within a heavily guarded military complex in Dhaka, it was originally the Joint Interrogation Cell (JIC), a military-run facility used for intelligence gathering. Over time, it was repurposed into a permanent secret detention center.

Another site, the Taskforce for Interrogation (TFI), has operated under the control of the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), an elite police force accused of extrajudicial killings and torture.

Also Read: Inside Bangladesh’s Shadowy History of Enforced Disappearances

Rights organizations, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, estimate that between 2009 and 2024, at least 600 people were forcibly disappeared in Bangladesh. Many of them were opposition politicians, activists, journalists, and members of the business community who had fallen out of favor with the government. Some returned—months or years later—broken, silent, and fearful. Others were found dead. And more than 150 remain unaccounted for.

For over a decade, the Hasina administration denied the existence of such facilities, dismissing allegations as “politically motivated.” In a 2022 letter to the United Nations, the government claimed that many of those reported missing had gone into hiding voluntarily, either to evade legal cases or due to family disputes.

That version of events began to unravel in August 2024, when Hasina was ousted from power following mass protests. Within days, former detainees began to emerge from secret custody, providing chilling details about the conditions inside Bangladesh’s hidden prisons.

“There Was No Time, No Light, No End”

For those who spent years inside Aynaghar and other detention centers, the physical scars are nothing compared to the psychological torment.

Mikel Changma, a leader of the United People’s Democratic Front (UPDF), was held for five years before being freed on August 7, just days after Hasina fled the country.

“For the first time in five years, I saw daylight,” Changma said. “Inside, there was no sense of time. No windows, no clocks. Just total silence.”

He recalled hearing distant screams of other detainees, their cries echoing through the halls. Guards rarely spoke. Meals were delivered through small slots in the doors. Those who resisted were beaten.

Former Bangladesh ambassador to Vietnam Maroof Zaman, who disappeared in 2017 and was released after 467 days, described being forced to sign blank sheets of paper—later used to fabricate statements against him.

“They wanted me to believe that I no longer existed,” Zaman said. “They took away my name, my identity. When I finally returned, I was a different person.”

Kamruzzaman and Firoz Mahmud Hasan, leaders of the Grameen Telecom Workers Union, were held in Aynaghar for seven days in 2022. They were told they would be released only if they signed statements implicating Muhammad Yunus, the country’s most famous businessman and a frequent target of Hasina’s government.

“They made us say that Yunus bribed us,” Kamruzzaman said. “Everything was scripted. We had no choice.”

Perhaps the most harrowing account comes from Abdullahil Amaan Azmi, a former brigadier general who was abducted in 2016 and held for eight years.

“I was blindfolded and handcuffed at least 41,000 times,” Azmi said. “They sealed off the only ventilation holes when they caught me trying to see daylight.”

For eight years, he lived in absolute darkness. The only sounds were the footsteps of guards and the muffled cries of others.

“They wanted us to forget who we were,” he said. “They wanted us to forget that we had ever existed.”

A Government Trapped by Its Promises

The revelations have placed the Yunus administration in a difficult position. The Nobel laureate has made clear his desire to investigate enforced disappearances and hold security forces accountable, but his ability to act remains in question.

In a November 2024 interview with Netra News, Yunus pledged full transparency, saying, “A commission has been formed, let the commission complete its work. After that, the detention centers will be open to everyone.”

However, sources familiar with government discussions say the military was never comfortable with this level of openness.

When the Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearance demanded that survivors be included in the inspection, military officials pushed back.

A January 29th memo from the commission, obtained by Netra News, warned Yunus that excluding victims would undermine the credibility of the investigation.

“An inspection without the concerned victims would not be effective,” the memo stated. “To avoid an embarrassing situation, the commission is unable to participate in the inspection.”

With the commission threatening to withdraw, the government backed down. The planned inspection, once hailed as a turning point, is now indefinitely delayed.

Families Continue Their Search for Answers

With the investigation stalled, families of the disappeared are taking matters into their own hands.

On August 6, members of Mayer Daak gathered outside the military intelligence headquarters in Dhaka, demanding information about their missing relatives. In response, the military proposed forming a “joint commission” to review cases—though no concrete timeline has been provided.

“We’ve waited for years,” said Sanjida Islam Tulee, whose brother disappeared in 2013. “We won’t wait forever.”

For now, Bangladesh remains a country haunted by its past. While some survivors have reemerged, many remain missing. Their families continue to search for answers, even as the institutions responsible for their disappearances remain unchallenged.

At a recent meeting with Mayer Daak, Yunus acknowledged the difficulty of delivering justice.

“Keep your hopes up,” he told them. “But I can’t say what the result will be.”

For families who have spent years searching for truth, it was a familiar response—one that leaves the fate of Bangladesh’s disappeared unresolved.